Ray Barretto: El Watusi

From Charanga Moderna (Tico, 1962)

Boogaloo Con Soul

From Latino Con Soul (United Artists, 1967)

Acid + A Deeper Shade of Soul

From Acid (Fania, 1967)

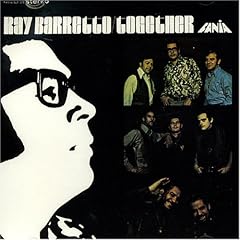

Together

From Together (Fania, 1969)

Cocinando

From Our Latin Thing (Fania, 1972)

Slo Flo

From Barretto Live: Tomorrow (Atlantic, 1976)

(Editor’s Note: Jeff Chang and I collaborated on the following post. I write the following:)

CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE READING…

Ray Barretto passed away on Friday from heart failure, at age 76.

With his signature, thick-rimmed glasses, Barretto never looked like what’d you expect from a king of Latin percussion: he seemed more like, well, your accountant maybe. Yet even if he never became as famous as his fellow conguero Mongo Santamaria, for many Latin music aficionados, he was just as revered, if not more, especially given a late career resurgence in the last five years. Barretto was also part of a larger wave of great percussionists to come out of New York, alongside Tito Puente, Willie Bobo and Sabu Martinez and of that bunch, none was as influential as Barretto in helping to push the Latin soul sound in the 1960s and ’70s.

Barretto’s early influences came out of the Latin jazz experimentations of the 1950s, specifically Dizzy Gillespie’s “Manteca” which became one of Barretto’s early hits during his years as a studio sessionist and sideman, recording for Blue Note, Riverside and Prestige. His emergence as a bandleader came with Riverside but it was his move over to George Goldner’s Tico Records (the king of Latin labels until Fania came along) that yielded Barretto’s first huge hit: “El Watusi”.

“El Watusi” was a charanga, one of the precursors to the boogaloo – you can hear on “Watusi” how boogaloo would build on the same basic elements as the charanga: piano-lead rhythm section, hand claps, and an irresistible dance groove (albeit at a much slower tempo).

Barretto rode the success of “El Watusi” for years: his next album for Tico was called El Watusi Man, two years later he released, Viva Watusi!. By 1967 however, Barretto had moved onto trying to capitalize on the boogaloo craze, recording his Latino Con Soul (a simple but rather genius title) for United Artists. “Boogaloo Con Soul” comes from that LP (the title is a bit redundant since, technically speaking, the “con soul” part is implicit in boogaloo songs). It’s a cool tune, one of the slower boogaloos out there, especially in comparison to Joe Cuba or Pete Rodriguez’s hits of the same era. It’s also longer than most, clocking in just over five minutes and in that respect, many of Barretto’s boogaloos nodded to his background in jazz and the longer compositions of the genre.

After Latino Con Soul, Barretto moved over to Jerry Masucci and Johnny Pacecho’s Fania imprint – then still a fledging label – and then released Acid which is, hands-down, the greatest Latin soul album ever recorded. I say this not simply because it had some of the best songs in the genre, but it was also a surprisingly consistent album. Many Latin LPs in the mid/late ’60s (and really, Acid is more of a post-boogaloo LP, especially in how it pushed the genre forward) tended to try to touch one at least three or four different dance rhythms: so you’d have a boogaloo or two here, a mambo there, a shing-a-ling there, etc. Acid, in comparison, was one of the rare albums of the era that embraced Latin soul (and jazz) wholeheartedly, not afraid to play the crossover card with songs that were clearly a meeting point between the Brown and Black musical cultures of New York. Barretto wasn’t alone in this regard – Joe Bataan would be another obvious example – but Acid ranks as the album that did it best.

The title track is a monster, blending both soul, Latin and jazz. I remember the first time I heard this: Chairman Mao was playing it at the Saturday night weekly he and Citizen Kane used to share at APT in Manhattan. I usually don’t try to sweat the DJ but when this came on, I had to ask Mao what the hell it was. Believe me, over a club system, the song is amazing.

The track wasn’t alone: other notable songs were the epic “Espiritu Libre,” the raucous “Soul Drummers,” fairly straight forward boogaloos like “Mercy, Mercy, Baby” and “Teacher of Love” and a personal favorite: “A Deeper Shade of Soul” (which became the source for a song by the same name in the late ’80s by a European group called the Urban Dance Sqaud).

Following Acid, Barretto put together several more Latin soul themed albums including Hard Hands, the compilation Head Sounds (which was basically a few key cuts from Acid plus a handful of new songs including “Drum Poem” and a version of “Tin Tin Deo”, and Together. The title song, “Together” is a stunner, not only for its fiery rhythm (which seriously kick ass) but listen to the song content: it’s a definitive post-Civil Rights Era anthem that I’ll put up against anything from James Brown.

(Jeff takes over from here):

Barretto’s records for Fania were some of the label’s firsts, and paved the way for the experimental, probing, but always relentlessly dance-able records to follow. Barretto found the groove and then opened it wide.

Fania Records ushered in the “Golden Age of Salsa”, and the historical parallels to what happened in hip-hop during the late 80s are striking. Salsa was a conscious effort to frame a particular world-view in sound: an Afrocentric brown-power music, if you will. Barretto’s contribution was key. Album manifestos like Que Viva La Musica and Barretto Power made him the KRS-One of salsa, to Eddie Palmieri’s Chuck D.

(You might even think of Willie Colon and Hector Lavoe as the Ice Cube and Dr. Dre of salsa. The very existence of the Fania All-Stars was extraordinary—as if the Stop the Violence Movement wasn’t just a one-off but a central, ongoing project!)

Just as importantly, Barretto helped shape Fania’s seminal sound, which was essentially a Puerto Rican update of classic Cuban music, extended into descargas or jams. To extend Oliver’s observation above, the sound was meant to move past the fast cycle of dance crazes into something more capital-I “Important”, something that was literally art for the people, in exactly the same way that P.E. set out to end an era characterized by fads like the Wop, the Cabbage Patch, and the Robocop with a conscious nod to a tradition of Black music and political struggle. Salsa took it black to the future.

One of Barretto’s biggest hits, “Cocinando”, alludes to Tito Puente’s “Oye Como Va” and Celia Cruz and La Sonora Matancera’s “Cha Cha Guere”, but extends the themes into a nice long solo vehicle. At once, the music is meant to be more contemplative and virtuousic. The version here by the Fania All-Stars—where I’ve edited in a brief interview with him at the beginning—is from the label’s biggest sound-and-vision statement, the movie feature Our Latin Thing (Nuestra Cosa).

In the mid-70s, now feeling stifled by salsa, Barretto left Fania. In a sense he was right on time. Groups like Santana, El Chicano, Malo, War, Earth, Wind & Fire, and War had taken Latin rhythms into the pop mainstream. And this was also the heyday of what would become known as the breakbeat—with Latinized, globalized funk coming from the Jimmy Castor Bunch, the Incredible Bongo Band, and Babe Ruth. The time had finally come for the sounds Barretto had pioneered during the 60s. In the liner notes to the classic 1976 live album Tomorrow, he wrote, “Gracias to la gente, the people who came out and kept us alive while they waited for the rest of the world to catch up!”

“Slo Flo” is a monster jam from that album. Barretto’s playing is masterful throughout, and this is an all-but-forgotten gem of the era, known mainly to serious Latin music heads and breakbeat fans. Like a lot of other Latin musicians, he migrated toward disco. It was simply the latest dance thing. A hustle anthem, “Stargazer”, is from 1978, and Barretto’s precision breakdowns would be imitated by house bands who played behind the earliest hip-hop records between 1979 and 1982.

Though he never got the credit, it’s hard to conceive of hip-hop’s backbeat these days without Hard Hands. He laid it down, and people followed, improvised on over it, whether with their sampling machines or their hips. He never asked for much more.

Be sure also to visit Captain Crate’s Barretto tribute.

chatter