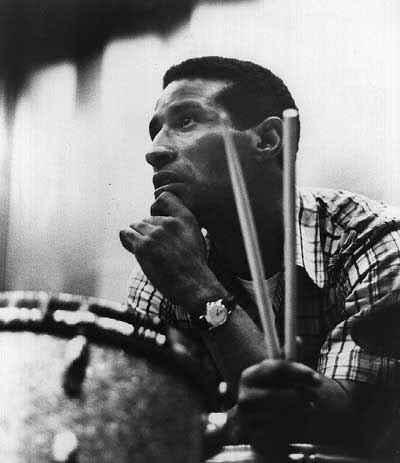

(Editor’s Note: This post was written by David Jaffe to commemorate the life, times and music of the late, great Max Roach)

Max Roach was one of jazz music’s great elder statesmen until his passing on August 15th of this year. His musical advancements in drumming were on par with trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie (who first brought Latin rhythms to jazz) and saxophonist Charlie Parker (who used syncopation in ways previously unimagined), with whom Roach came to prominence. Roach fronted several important bands, and it is likely that only fellow bop drumming pioneer and contemporary Art Blakey was a leader-drummer of as many significant lineups. Roach was also an outspoken activist for racial equality, a musical experimenter, and jazz educator until the end of his life.

Charlie Parker: Dexterity

From S/T (Warner Bros, 1977)

Depending on which discography one is reading, Roach first rose to prominence in the bands of Duke Ellington and Benny Carter during the early ’40’s, although it is likely the influence of Coleman Hawkins, one of the few greats of the Swing generation to move fluidly into the new style bop, was of the greatest significance. Most writers will point to the jam sessions at Monroe’s and Minton’s with Gillespie, Parker and Pianist Thelonious Monk in the mid ’40’s in New York as the birth of bop. The recordings that ultimately sprouted from the seeds of those jam sessions are most famously with Charlie Parker and later, Miles Davis. Listening to the early Roach recordings gives the sense of both the drum kit floating along with the music and giving it drive at the same time. It is Roach’s use of the cymbal along with the bass and snare that provide the propulsive movement. The chick-a-boom rhythm of swing had always provided momentum to jazz, and in many ways is one of jazz’ defining characteristics, but Roach brought a new sense of movement with his accent on cymbals and ability to layer textures of percussion that was new to jazz.

Max Roach: Drum Conversation Pt. 2

From Autobiography In Jazz (Debut, 1954)

Charles Mingus & Thad Jones: One More

From Jazz Collaborations Vol. 1 (Debut, 1952)

In the early ’50’s Roach became an owner of Debut Records along with Charles Mingus, the label on which Roach would debut as a leader and which would issue the Massey Hall concert recordings. The Debut Massey Hall records are a holy grail for bop diggers, both for scarcity and for the quality of the music within the grooves. It is not hyperbole to say that the performances on this disk are some of the best in the jazz cannon; all of the players, Roach included, are in top form. Also, listen to the give-and-take stop-time soloing with Thad Jones on One More, also issued on the Debut label.

The next two major phases in Roach’s career were his band with trumpeter Clifford Brown, and the remaining bands that Roach lead following Brownie’s death. Brownie was a unique voice in jazz who could play solos on ballads fast and up-tempo solos slowly with a fat, warm tone, and who, despite his young age, had a style of his own. The car accident that took Brownie also killed pianist Richie Powell (great jazz pianist and fellow bop pioneer Bud Powell’s brother), devastating Roach. Not only was Brownie close to Roach, but the pair shared a musical simpatico that combined the lyricism of Brown and the drive of Roach.

Max Roach Plus Four: Lover

From Jazz in 3/4 Time (Emarcy, 1957)

With great effort Roach soldiered on after Brown’s death, establishing some fantastic bands that provided Roach the opportunity to further develop his drum stylings. During this period Roach experimented with 3/4 time and with continuing to place drumming in the context of multiple, reinforcing textures. Rhythms are played on every part of the trap set, including the stands, and with a wide variety of sticks, brushes and mallets. Roach’s post-Brown bands include a who’s-who of great jazz musicians including Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins, Booker Little, Oscar Pettiford, George Coleman, and Hank Mobley. In all of these recordings, multiple rhythms are played at once on different parts of the drum set, each pattern having its own logic while still providing propulsion to a given tune. Roach was even able to play a single part of the set for an extended solo in such a way a to completely hold a listener. Check out how on the drum solo on Lover the different rhythms skip from one to the next but never loose the beat of the song as a whole.

Max Roach: Freedom Day

From We Insist! Freedom Now Suite (Candid, 1960)

Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Max Roach: Money Jungle

From Money Jungle (United Artists, 1962)

Max Roach & Archie Shepp: Suid Afrika 76

From Force (Base, 1976)

In the ’60’s Roach was actively involved with civil rights. He recorded several lp’s, including his own We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite for Candid and Money Jungle with Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus, where the theme was pain of racial inequality. These recordings foreshadowed many of the protest records that were to follow in all styles made by Black men and women in America in the following decades. So profound were civil rights to Roach that he would continue to explore its themes for the remainder of has career, including the protest albums Force, an extended duet with Archie Shepp, The Loadstar, and Sonny Rollins’ Freedom Suite. The drum solo on Freedom Day almost mimics the breaking of the shackles of slavery days, while the drum intro on Suid Afrika uses brushes to mimic the sounds and rhythms of African tribal drumming ˆ for four minutes! Money Jungle is significant because it is an Ellington tune. Ellington, one of the greatest composers in American music was not known as a protest artist, but rather as a dance-band leader and master arranger. Try to hum the melody to the Ellington composition Take the A-Train while listening to outrage expressed by all three musicians on Money Jungle.

Roach continued his career almost until his death with innovative projects like the all-drum M’Boom, experiments in free jazz, and as an educator at both the Lenox School of Jazz and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Certainly, a great deal of ink has used to recall Max Roach’s great humanity and his profound influence on music. It is with a profound sense of both Max Roach’s importance as a musician and character as a man that we say: Peace be with you, Brother Max.

–David Jaffe

chatter